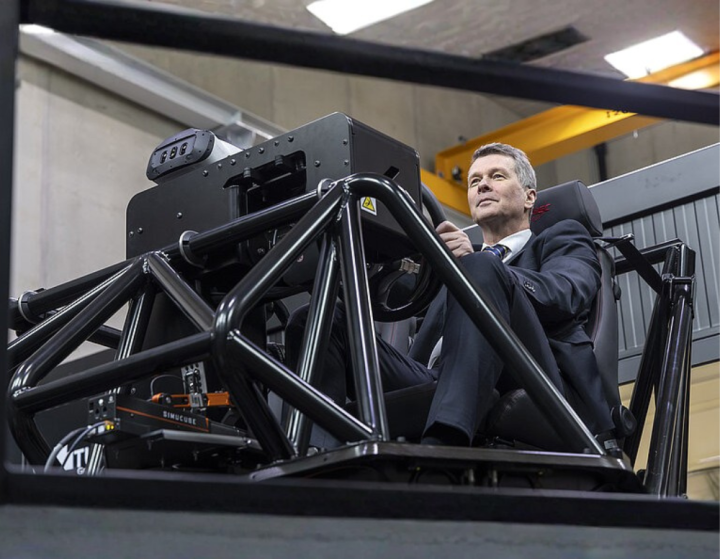

The system looks like a high‑end racing game, but underneath the glossy graphics lies a laboratory that can fool even seasoned test drivers. Built jointly by Graz University of Technology and the globally recognised mobility firm Magna, the unit is housed in a purpose‑built simulation centre. Its cabin mirrors a production car down to the stitching on the steering wheel, the resistance of the brake pedal and the feedback from the chassis. Engineers sit inside, strap in, and the whole rig moves in sync with the virtual road.

That matters because the tactile cues—road‑feel, vibration, torque surge—are the last things a purely software‑based model can deliver. When you can feel a pothole before it exists in the real world, you can redesign suspension geometry, tweak motor torque curves, or even re‑engineer the interior layout without ever stamping a prototype.

The heart of the system is a set of six movable struts that actuate the cabin in three dimensions. When the virtual car accelerates, the struts push the driver back, when it brakes they pull forward, and when the road surface changes they tilt the whole cockpit. Sensors monitor the driver’s inputs and feed them back to the simulation engine in 3‑4 ms, a latency low enough that the brain registers the motion as genuine.

A second breakthrough is the vibration bandwidth. The rig can generate frequencies up to 100 Hz, a range that captures the subtle hum of an electric motor and the fine‑grained tremor of road texture. Traditional simulators top out at 30 Hz, meaning they miss the whisper of an EV’s single‑speed drivetrain. Here, engineers can hear that whisper, feel it through the seat, and decide whether additional acoustic damping is needed.

Why it matters: electric cars lack engine noise, so the driver’s perception shifts to vibration and road feel. This simulator reproduces those cues with startling fidelity, giving engineers a new lever to fine‑tune comfort and safety.

Electric propulsion changes the sensory landscape. Without a combustion roar, the torque instantaneity and the low‑frequency vibrations become the primary feedback channels. The simulator’s ability to emit over 100 Hz of vibration means designers can evaluate how a new battery pack placement influences chassis stiffness, or how regenerative braking feels at the pedal.

A bullet list of immediate benefits:

The centre also runs photo‑realistic traffic environments powered by virtual reality. Drivers can weave through a congested cityscape, negotiate a mountain pass, or cruise on a highway while the system reproduces every bump, curb and lane marking. The visual fidelity combined with tactile realism creates a holistic test bed that no traditional wind‑tunnel or static rig can match.

The launch arrives at a time when automotive market is flirting with its first mass‑produced electric cars. Local manufacturers and importers are scrambling for validation tools that keep pace with global standards. By offering a shared facility, the simulation centre lowers the entry barrier for smaller firms that cannot afford an in‑house rig.

Competitive context – While Europe hosts a handful of high‑end simulators, none combine the low latency, high‑frequency vibration and full‑scale cockpit in a single package. The nearest alternative in Asia sits in Japan, but it lacks the 100 Hz capability. For engineers, this means a first‑mover advantage: faster development cycles, better‑tuned vehicles, and a stronger case for government incentives on EVs.

The centre plans to open its doors to car manufacturers, motorcycle makers, and research universities by the second quarter of 2026. A subscription model will grant scheduled access, while a limited number of public demo days will let enthusiasts experience the technology firsthand. The expectation is that by 2027, at least four major brands will have logged over 500 simulation hours each, translating into tangible product improvements.

The project moved quickly from concept to reality. Below is a concise roadmap that shows where we are and what lies ahead.

| Phase | Date | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Installation | January 2026 | Completed |

| Public Demo | 15 February 2026 | Live |

| Manufacturer Access | Q2 2026 | Planned |

| Full‑scale Rollout | 2027 | Projected |

The next milestone is a collaborative pilot with a local EV startup, slated for June 2026. The partnership will test a new battery‑thermal‑management system inside the simulator, allowing engineers to feel the subtle shift in cabin temperature as the pack heats under load. Success could fast‑track the startup’s market entry, giving Nepal its first home‑grown electric sedan.

What’s next – Expect a cascade of announcements as more OEMs sign up. The centre will also host a technical symposium in late 2026, where global experts will share best practices on virtual prototyping. For the Nepali automotive ecosystem, the message is clear: the future will be tested long before the first bolt is tightened.

Q: When can manufacturers start using the simulator? A: Access for car makers begins in Q2 2026 after the public demo period. Scheduling is handled through a subscription portal on the centre’s website.

Q: Is the simulator limited to electric vehicles? A: No. While its high‑frequency vibration is a boon for EVs, the system can emulate combustion‑engine torque curves, hybrid powertrains and even conventional gasoline models.

Q: What are the pricing tiers? A: The centre offers three packages – Basic (10 hours/month, $2,500), Professional (30 hours/month, $6,800) and Enterprise (unlimited access, custom pricing). Exact figures are published on the centre’s pricing page.

Q: Will the simulator be available for academic research? A: Yes. Universities can apply for a research grant that provides up to 20 free hours per month, encouraging local talent to explore automotive engineering.

Q: How does the system handle different road surfaces? A: The VR engine contains a library of over 150 road‑type models, from smooth highway asphalt to rough mountain gravel. Each surface triggers a unique vibration pattern that the struts reproduce in real time.

Q: Does the simulator support motorcycle testing? A: A dedicated two‑wheel module is under development and expected to be operational by early 2027, expanding the centre’s reach to the two‑wheeler market.